When George W. Bush was elected Governor of Texas on a law and order agenda in November of 1994, convicted bank robber Dennis Wayne Hope wrote to his mother that he now had no hope of ever making parole. Those were his words – no pun intended.

The 26-year-old Hope had been training for months for this moment. He ran countless laps around the prison recreation yard of the Darrington Unit as if he was training for a marathon.

If the rifle-toting guards atop sentry towers had watched closely, they would have seen Hope drop a small rock out of the pocket of his white prison-issue pants every ten laps.

Hope had calculated that ten laps equaled one mile. The blue-eyed, five-foot-eight-inch, 152-pound inmate would run ten miles at full speed daily.

Back inside his cell, Hope counted off hundreds of pushups and handstands.

Few Texas convicts have ever successfully escaped because they only had a plan to reach the prison wall and nothing beyond it.

Hope would make one of the most daring escapes in the history of the Texas prison system.

Darrington was originally a Civil War-era plantation. Convict labor leased from the Texas Prison Commission supplanted slave labor there.

In 1918, the Prison Commission purchased the 6,747-acre plantation located south of Houston.

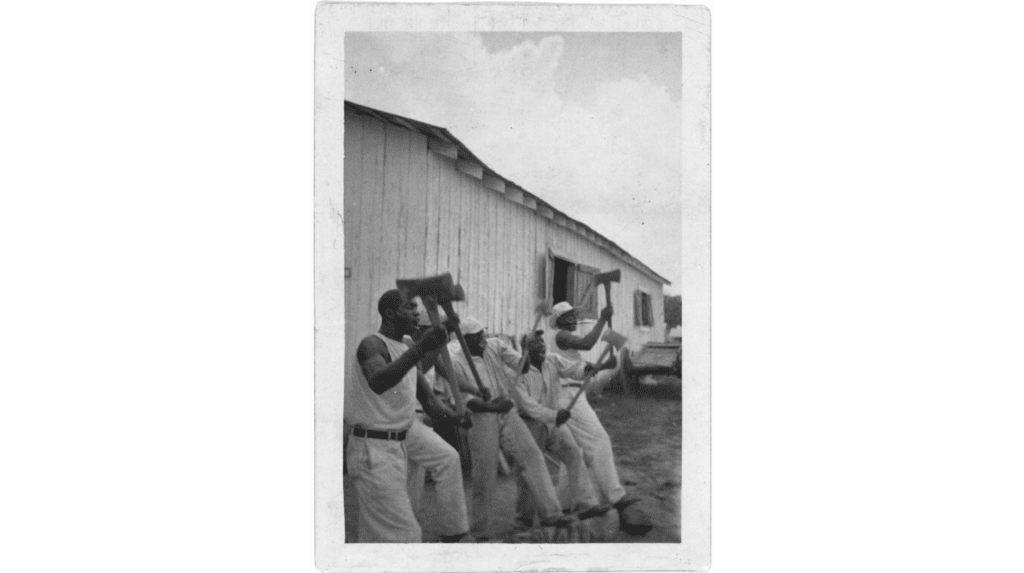

Folklorist John Lomax and his son Alan recorded work songs by African American convicts during the Depression in 1934 as they chanted to the swing of their axes.

A prisoner called Lightnin’ Washington by his fellow inmates who said he could think faster than the warden led a song called, “It’s a Long John”, about an escape from bondage

The Texas Department of Justice (TDCJ) recently changed the prison’s name because of its roots in slavery.

Today, inmates still raise cows, pigs, and poultry here. And work the fields, planting and harvesting crops.

John Moriarty, the former Inspector General of the TDCJ, recalls, “the Texas prison used to be self-sufficient. They grew their own food and raised their own cattle and sheep, and hogs. Back then, they had the third-largest hog operation in the world.”

Hope timed his escape for the Thanksgiving holiday in 1994 when Darrington was on a skeleton security shift. Most of the unit’s 425 guards cooked turkey and dressing at home with their families.

Gregory Ott, an inmate trustee, was inside the prison boiler room, filling a water sample for a daily test.

At about 9:05 PM, the doorbell to the boiler room buzzed.

Ott thought it was a guard making rounds and opened the electric lock.

Inmate Jason Montgomery pushed in the door, followed by Dennis Hope.

Montgomery was serving a life sentence for attempted capital murder.

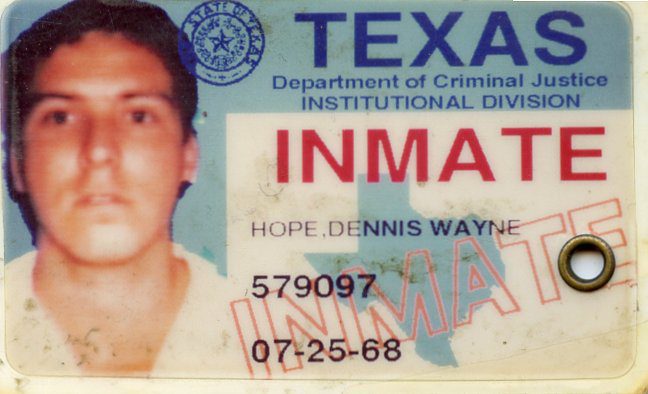

Hope was serving an 80-year sentence for armed robberies.

Hope grabbed Ott from behind. Put his arm around his neck. Forced him to the floor.

And said, “I was told just to kill you, but I’ve got nothing against you. Lie there and shut up, and you won’t get hurt.”

Hope and Montgomery tied Ott’s hands with electrical wire behind his back and legs.

And bound his hands with electrical tape.

They wanted to know if all of the prison lights would go out when the electric power was shut off.

Ott replied yes, but he was afraid the boiler would blow up.

Hope and Montgomery pulled green prison blankets out of their shirts and tied them around their legs to protect themselves from razor-sharp concertina wire atop the prison’s security fence.

The doorbell buzzed again, and a third member of the escape plan, Harry Decker, showed up.

Decker was serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery.

The trio wore dark clothing with hoods made of blankets to cover their white prison uniforms.

They sabotaged the backup power generators and flipped off the master electrical switch in the boiler room. The massive prison turned pitch black.

The fog was rolling in as Hope sprinted one hundred feet to an interior fence. He cut a hole in it with wire cutters stolen from the prison maintenance shop.

He slipped through the hole and quickly scaled the exterior fence like a monkey.

Meanwhile, Inmates Montgomery and Decker were out of breath and couldn’t follow Hope over the exterior fence.

Finally, they cut a hole in the fence and squeezed through it.

At 9:30 PM, a guard in a picket tower located 100 yards spotted the pair.

He ordered them to halt and fired a warning shot with his rifle.

They briefly stopped and started running again. The guard fired four more rounds.

Decker fell to the ground crying out that he had been shot in the foot.

Montgomery crawled back to help him. Decker hadn’t been shot. He had sprained his ankle.

The pair got up and started running again.

The guard fired four more rounds but missed in the darkness.

The prison turned loose its specially trained bloodhounds. Montgomery and Decker were caught near the prison within two hours.

John Moriarty, who led the hunt for the escapees, says Hope used the two out-of-shape inmates as a diversion. “They were basically dog meat because he knew that the minute that they went over the wire, the dogs would be put on the ground, and they would be tracking them.”

Hope was long gone. He ran 8 miles across rough wooded terrain at a fast clip.

He swam across a canal and rolled in the dirt to turn his white prison garb brown.

Hope then ran 13 more miles to Pearland, Texas south of Houston.

He lived off of hamburger buns thrown out from a Mcdonald’s and hid in the weeds.

He watched a service station for the next customer to leave keys in the ignition.

When a GMC pickup truck driver went inside to pay the cashier.

Hope slipped behind the wheel.

He had a long head start on fugitive hunter Louis Fawcett.

The prison system had just assigned Fawcett to the FBI’s Violent Crime Task Force in Dallas.

Hope’s case was the first to land on his desk. “The Escape itself was very clever. He was determined to get away or was going to die in the process. I really believe that.”

Dennis Hope had been a grocery store stocker in Dallas. When he got passed over for a promotion, the 22-year-old retaliated.

He knew where money was kept and the schedule when armored cars would pick up daily deposits.

He robbed four supermarkets at gunpoint, some of the very ones where he had worked. And fired a round into one store as he left.

In two other robberies, Hope dressed up in a uniform stolen from an armored car company.

He called a grocery store manager, telling him that the regular armored car was running late and he was the substitute.

Hope walked out with $29,200 in cash from the first robbery and $37,000 in the second robbery.

The real armored cars would roll in shortly after Hope had made his getaway.

Later that month, a Dallas police detective spotted Hope wearing a shoulder holster with a Ruger 6 blue steel revolver in the Borrowed Money Bar nightclub parking lot.

Hope claimed he was a sheriff’s deputy. He flashed a small badge with “special police officer” written on it and produced a pair of handcuffs.

The detective arrested him on the spot for impersonating an officer.

Behind bars in the Dallas County jail, Hope arrogantly demanded catered meals and television for his cell.

Five months later, on his way to trial, Hope vanished from a line of prisoners handcuffed together at the Dallas County courthouse.

He used a key smuggled into the jail, hidden in his mouth, to get out of the cuffs.

Hope stripped off his white prison overalls to his boxer shorts and jogged

through downtown Dallas.

Fawcett says Hope convinced an officer searching for him that he was an attorney out for his daily run. “A policeman pulled up beside him. Hope told the officer that he was training for a Triathlon. He exchanged a polite conversation and was allowed to jog away.

Hope’s escape ended in a high-speed chase when a State Trooper shot out the tires of his stolen car.

In 1991 Hope was sentenced to 80 years in prison on four counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon and four thirty-year sentences for stealing 20-grand dressed like an armored car guard, impersonating an officer, escape, and car theft.

Taking no chances, the Dallas County Sheriff transported Hope to the Texas Prison System Intake in Huntsville, Texas, wearing handcuffs, leg irons, and a belly chain.

He was sent to the Darrington Maximum Security Unit due to his high escape risk.

Fawcett and Moriarty knew from experience that fugitives are a creature of habit.

They return to family, fellow ex-cons, and girlfriends.

Hope returned to Rockwall a suburb of Dallas.

He bought a BB gun and used it to rob one of the grocery stores he originally had been convicted of robbing.

Hope brazenly entered a grocery store with a marked Irving Police patrol car parked in front.

He held up a clerk for $1300 and calmly walked past the police officer.

Hope drove a car he had carjacked to a vantage point from where he watched and laughed as the grocery store’s employees ran outside to tell the officer in the parked patrol car that they had been robbed.

Lawcett says it was payback for his 80-year prison sentence. “Hope didn’t feel like he deserved that much time. He said he didn’t hurt anybody. My response to that is when you aim a gun at a young girl, you hurt her. She’s terrified. That will affect the rest of her life.”

The FBI launched a statewide dragnet for Hope.

Crimestoppers posted an award.

Grocery stores posted wanted posters across the Dallas metropolitan area.

Investigators followed up on dozens of leads and sightings of Hope.

They interviewed ex-wives, ex-girlfriends, family members, friends, work associates, and his fellow inmates.

One ex-girlfriend told them that Hope lived three different lives: husband and Christian image, rich man’s son to his girlfriends, and top thief in town.

FBI SWAT teams staked out dozens of grocery stores, waiting for Hope’s next move.

He thumbed his nose at them by robbing grocery stores nearby that were not under surveillance.

Moriarty and Fawcett tracked Hope to Memphis, Tennessee, which he used as a home base for his Dallas robberies.

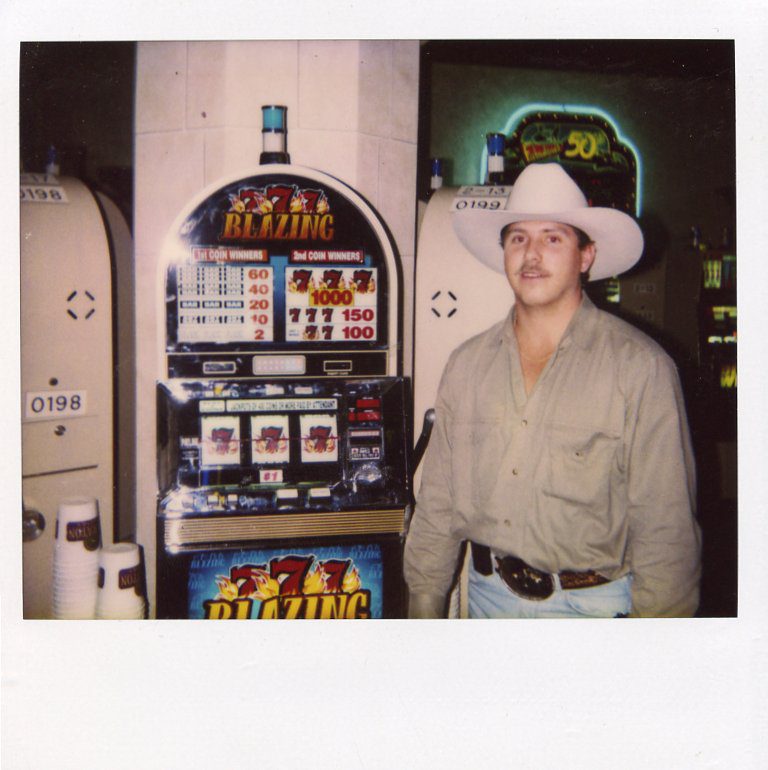

He was charming women and spending thousands of dollars from the robberies at casinos in Tunica, Mississippi, a short drive south of Memphis.

Like a scene from the movie Cool Hand Luke, Hope mailed letters and fifty-dollar money orders to his friends back at Darrington, bragging about his cool life outside.

He signed one as Your Bro. Dangerous “D.”

On another letter, the return address in Hope’s handwriting was Irk Megclerk from 1269 Drop Trousers, Austin, Texas.

Another letter contained the PS message: Big Bank Hank

It was a code that Hope had recovered money hidden from an earlier armored car robbery.

But for all of his bravado, Hope got homesick at Christmas. And made a mistake.

Moriarty’s electronic surveillance traced Hope’s location to a new girlfriend’s phone at her employer’s office to phone an old girlfriend. “He was definitely a womanizer. And the old saying that ‘women love outlaws’ really applied in this circumstance. He played that cowboy image, and he was a con man.”

Hope drove a black Jaguar purchased with stolen loot. He told his new girlfriend in Memphis that he owned a country-western bar in Dallas.

When Moriarty and Fawcet pulled into the parking lot of the Denim and Diamonds country-western nightclub in Memphis, they spotted a black jaguar. The butt of a 45-caliber automatic pistol was sticking out from under the front driver’s seat.

Denim and Diamonds was the largest country western club in Memphis. It was packed with tough-looking cowboys.

Moriarty fit right in. He worked undercover and looked like an ex-con – bearded with long hair. He used the “F” word as a comma in conversations.

Fawcett didn’t look much different and certainly nothing like a cop.

Far across the 31,000 square foot dance hall, Moriarty spotted Hope wearing a white straw cowboy hat.

He stood at a table holding court—the center of attention.

Moriarty and Fawcett put Hope in handcuffs before he knew what was happening.

Fawcett looked hope in the eye, “He was shocked. I told him I said you’re going back to Dallas. Your name is Dennis Hope; you’re going back to Dallas with us. And he was shocked. He didn’t argue. He didn’t resist. I expected we might have a fight on our hands, but he was not armed.

Nearly nine hours after arriving in Memphis and running down dozens of leads, Moriarty and Fawcett took Hope into custody at 11:45 PM on February 2, 1995.

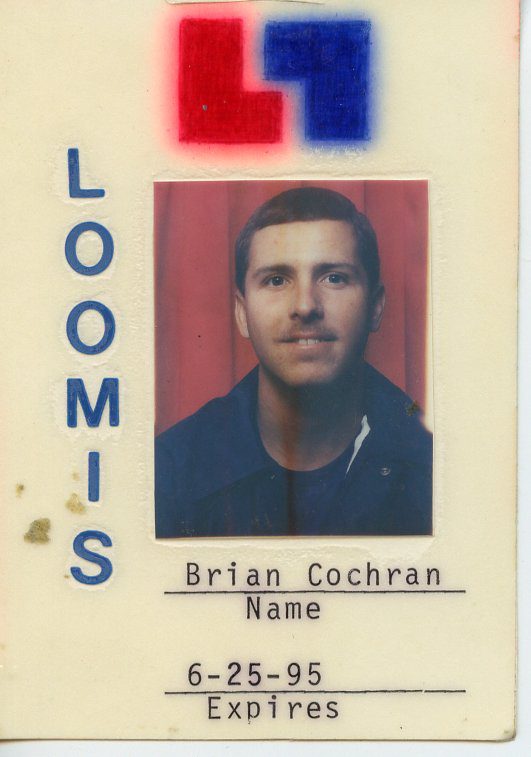

The investigators found a treasure trove of evidence that would send Hope to prison for the rest of his life, including fake armored car guard uniforms and ID cards for his next robbery.

I interviewed Hope when he arrived at the Dallas County Jail. He told me to tell the FBI that he was planning his next escape.

Then Jail Commander Bob Knowles was worried, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody that has spent the time to plan as he does, and he is very patient.”

Hope had resumed his daily regimen of running in place for hours and doing hundreds of pushups and handstands.

I asked him how he had gotten out of handcuffs and escaped from jail the last time he was here. Hope asked to borrow my ballpoint pen. He removed the plastic ink cartridge. With a few twists and turns Hope shaped it into a handcuff key.

On the way to court, Hope picked the pocket of a Sheriff’s Deputy for a key.

In my broadcast TV news report, I asked Hope, It sounds like you are already looking for the opportunity to make a run for it again. Will you be back?”

Hope replied, “I’m not going to stop trying. And I look at this as if they kill me and I am trying to get away, and they do kill me, then the state still didn’t get the 80 years out of me.”

After watching this on my news report, the Dallas County Sheriff ordered the FBI to move Hope to a federal holding facility where Hope almost escaped again. He hacksawed through doors, assaulted a guard, and took over the jail’s command post.

On August 18th, 1995, a seven-man, five-woman federal jury deliberated for less than an hour before convicting Hope on eight counts of robbery, felony possession of a firearm, and carjacking.

During the four-day trial, the jury was shown my televised interview with Hope.

Federal prosecutor David Finn called Hope cagey, dangerous, and savvy. He urged the jury to put an end to this one-man crime machine. “He is essentially the equivalent of the energizer rabbit. He keeps going and going both in and outside of prison.”

U.S. Marshals had to strap Hope to a bare chair in the federal courtroom.

The leather cover had been removed so Hope could not pry loose an upholstery tack to use as a weapon.

Before the verdict, he scuffed with officers.

And threatened to stab his court-appointed attorney in the skull with a pencil.

The judge stacked a 72-year federal prison sentence on top of Hope’s 80-year Texas sentence.

Hope was still defiant when I interviewed him inside the Supermax Telford Unit in rural northeast Texas a year later.

The Telford Prison unit looks like a massive concrete bunker surrounded by rings of security fences and rolls of razor-sharp concertina wire.

Hope found himself under the custody of Jack Garner, who was then regarded as one of the toughest prison wardens in Texas. I asked Garner, “What do you do with Dennis Wayne Hope, who has nothing to lose?” Garner replied, ”My opinion is we lock him up right where he is at and throw away the key. Dennis Wayne Hope should never get out of the penitentiary.”

Hope was locked into Administrative Segregation, a prison within a maximum-security prison.

I have witnessed the restrictions described by John Moriarty, “You spend 23 hours a day alone in a single cell. You are escorted out under heavy guard for one hour to shower and recreate. It’s the bowels of the prison. And you’re afforded all of the care required by law, but it’s the tightest security the prison system has.”

Guards deliver meals through a locked window called a “bean slot,” opened by a wrench on the door.

It’s not uncommon for some inmates to mentally break from isolation.

The first time I went into administrative segregation, the noise is what struck me. It was initially intimidating – almost like entering a dog pound full of angry pit bulls. Some inmates through urine and feces on the guards.

Warden Garner was not a bit worried about Hope escaping.

He beamed with pride that an inmate escaping from him to Mexico a decade earlier had just been captured.

The Warden had kept the inmate’s photograph in his wallet as a reminder and pledged that Hope would never get away,

Dennis Hope confidently told me that the old-time wardens like Garner would retire someday.

The prison system would forget about his notorious escapes.

He would bide his time and plan another break for freedom.

In a 2009 letter to a British television producer interested in his story, Hope stated, “In some areas, I threw caution to the wind. To me, life is defined by more than just a heartbeat. It’s about living and enjoying some, if not all, of what you do. It would serve no purpose to be on the lam if I were just hiding under a rock. I never had any intentions of coming back to prison. I’d either be dead or exercising my freedom somewhere in the United States.”

Dennis Wayne Hope is 54 years old at the time of this writing. He has spent more than 27 years in solitary confinement. Hope has been denied parole for more than 15 years.

In February of 2022, he unsuccessfully asked the U.S. Supreme Court to consider whether such prolonged isolation violated the Eight Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment.

Hope is pictured with a strong jaw and short salt-and-pepper hair in his most recent prison mugshot.

He wrote to his lawyers that “challenging the use of solitary confinement has given me a purpose and goal and helped me maintain a degree of sanity in an otherwise insane environment.”

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Hope’s case, but he has been released back into the prison system’s General Population from Administrative Segregation.