The 1930s were a time of great turmoil and transition in America. The Jazz Age had ended, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) pushed through the repeal of Prohibition, but the country was in the grip of the Great Depression. Amidst this backdrop, a new breed of criminal emerged. These were not the pseudo-businessmen of the Prohibition era but rather desperate, often uneducated young men from rural areas. They embarked on robbery and kidnapping sprees, hitting with fury and precision that left the country reeling.

The Emergence of John Dillinger

John Dillinger was the most famous outlaw of the 1930s. This charming yet elusive bank robber captured the public’s imagination and fueled an entire genre of crime melodramas during the darkest days of the Great Depression. Unlike the stereotypical gangster, Dillinger was quick, athletic, and charismatic, making him a natural leader among his peers.

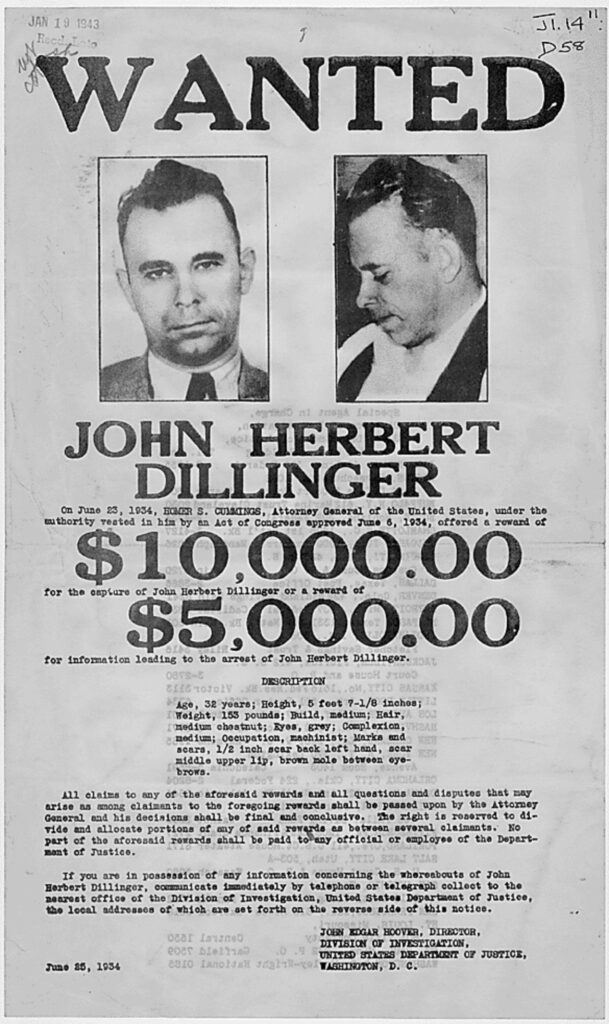

The press nicknamed him “jackrabbit” for his ability to leap over bank cashier’s windows. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover dubbed Dillinger “Public Enemy Number One” and plastered post office bulletin boards with his wanted poster.

A Troubled Childhood

Like so many gangster yarns of the Great Depression, Dillinger’s story begins with a troubled childhood full of promise cut short. Born on June 22, 1903, in Indianapolis, Indiana, he was the younger of two children. His father was a stern, somewhat distant figure—an ambitious grocer who worked long hours building his business. Tragedy struck just after Dillinger’s fourth birthday when his beloved mother died suddenly from a stroke.

The Formative Years

Despite early upheaval, outward signs pointed to a stable, successful life ahead for Dillinger. He consistently earned high marks at the local elementary school, and his baseball prowess earned the admiration of his classmates. However, Dillinger had a restless streak that quickly led him into trouble. At twelve, police hauled Dillinger before a judge for stealing coal from a rail yard and peddling it door to door. The judge sent him home with a dire warning: “Watch your step, young man.”

Teenage Rebellion and Early Crime

As his teen years approached, Dillinger’s rebellious streak only grew. He ran off to enlist in the Navy during World War One at just 16 but deserted within months. Bored and restless, Dillinger dropped out of high school a year shy of graduation and drifted from one menial job to the next. His path might have straightened out with marriage to teenager Beryl Hovius and the prospect of fatherhood in 1924. However, the idyll was short-lived. Dillinger chafed at domesticity, squandering his nights drinking and partying.

The First Heist and Imprisonment

His penchant for risky thrill-seeking reached its apex when a drunken grocery store heist with an ex-con buddy went south. Though the bungled holdup netted no money, Dillinger was promptly collared and sentenced to a 10 to 20-year prison term. Little did he know his true education in crime was just beginning. Prison would be the crucible in which the rash young punk was forged into the hardened career criminal destined to become Public Enemy Number One.

The Making of a Master Criminal

Incarcerated at the Indiana State Reformatory in Pendleton, an embittered Dillinger vowed, “I won’t cause you any trouble—except to escape.” His audacious reputation preceded him, and he caught the eye of seasoned bank robbers Harry Pierpont and Homer Van Meter. They schooled him in the finer points of their chosen profession. Dillinger proved an apt pupil in their informal master class on lawbreaking. He emerged in May 1933 after 8 1/2 years behind bars, a changed man—now cunning and hardened, a fully-formed outlaw.

The Dillinger Gang

Dillinger launched his bank-robbing career in earnest that fall. His string of solo heists across Indiana impressed his former mentors. By October, he’d amassed enough cash to launch a prison break. Pierpont, Van Meter, and six other inmates blasted their way out of Michigan City with smuggled guns. The Dillinger Gang blazed a yearlong trail of bank jobs across the Midwest, making them the most famous—and feared—outlaws of the Great Depression.

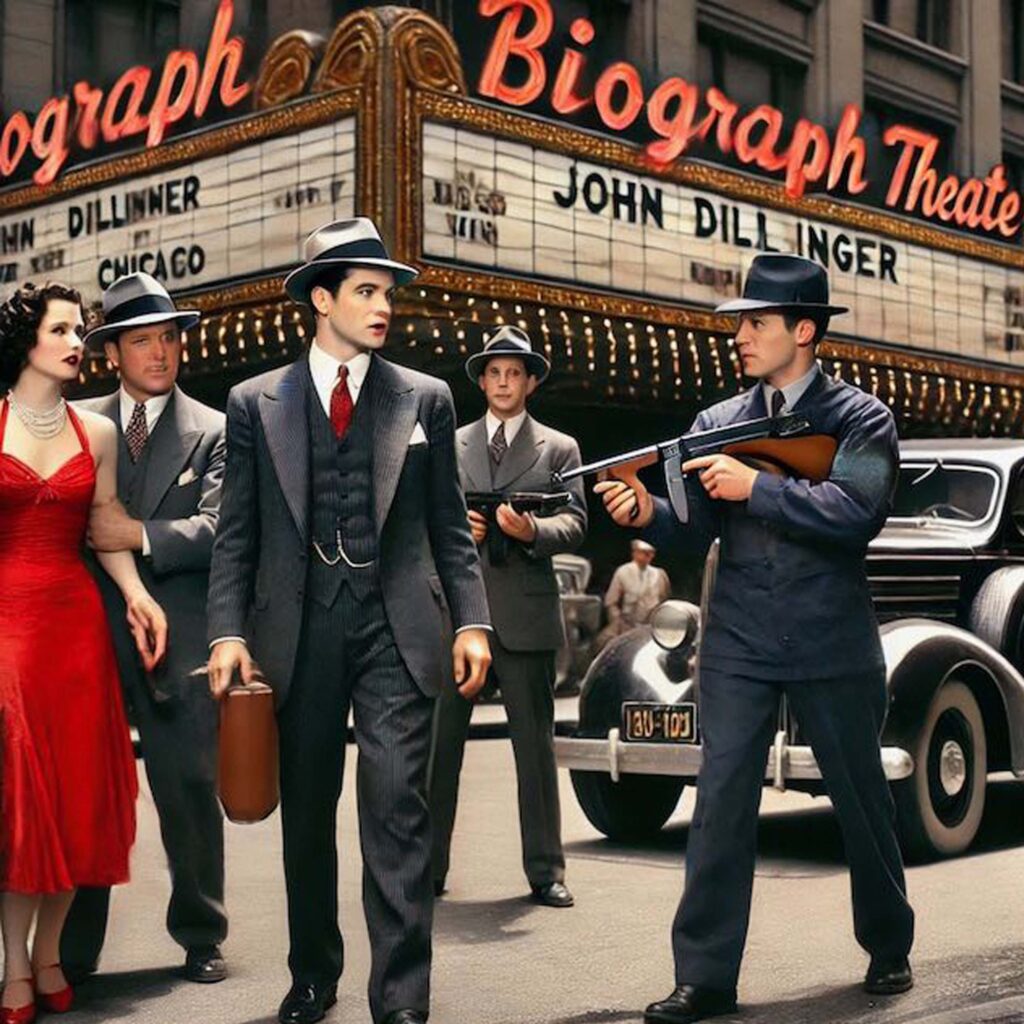

Dillinger became known for outgunning police by using .50 caliber Thompson Submachine guns.

The Height of Dillinger’s Notoriety

One close call came after a botched robbery in East Chicago left a cop dead. Though Dillinger was likely not the triggerman, the FBI slapped him with his first murder charge. Recognized by firemen from his wanted poster after a hotel blaze, Dillinger was nabbed with half the gang in Tucson and hauled back to Indiana’s Lake County Jail in Crown Point. Publicly, he shrugged off any worry, posing for reporters alongside the warden and cracking wise. Privately, he knew his luck had run out.

The Famous Escape

The Crown Point job would become the most famous of all Dillinger’s great escapes. He carved a fake gun out of the wooden shelf of his cell, stained it black with shoe polish, and used it to bluff his way out. The jailbreak burnished his legend as a master escape artist. The FBI officially targeted him for arrest under the Dyer Act, and in desperation, he turned to an underworld plastic surgeon. However, the crude disguise of scars and dye job was hardly the transformation he’d hoped for.

The Final Days

The trap was sprung on the night of July 22, 1934, amid a stifling midsummer heat wave. Dillinger, sweating through his shirt and his face still numb from the botched surgery, was in no condition to spot the setup. Sage suggested they take in a movie at the Biograph Theater downtown. Dillinger let himself get lost in the film, but any peace the cinema afforded proved fleeting. The gunfire echoed off the brick and mortar of the alley like cannon fire in the still night.

When the smoke cleared, the man lay face down on the cobblestones, blood pooling beneath his shattered face. Just like that, the legend of the unstoppable John Herbert Dillinger had written its final chapter. Or had it? Even before the celebrated bandit’s bullet-ravaged corpse was cold, rumors swirled that the FBI had slain the wrong man. Skeptics claimed the body displayed as Dillinger’s bore only a passing resemblance to the dashing rogue.

Conclusion: A Myth in American History

Whatever his true fate, Dillinger would become more prominent in death than he’d ever been in life. His bloody demise assured his immortality and forever fixed him in the popular imagination as the cocky, smiling bandit eluding death and the law. In death, he transcended his mortal failings to become a symbol, a spirit, an ideal of individualism and rebellion. In short, he became a legend. John Dillinger will forever be on the run, one step ahead in stories from Robert Riggs’ Crimes Through The Ages.