This true crime story is not about a heist pulled off by a notorious bank robber or a cunning scam artist—but an audacious act of bureaucratic theft that spans generations.

More than $30 billion in matured U.S. savings bonds, investments made with trust and patriotism, are sitting unclaimed. The rightful heirs, families like mine and maybe even yours, are stonewalled by the very institution that promised to safeguard these assets.

The U.S. Treasury, armed with meticulous records of bondholders, holds fast to those names while demanding an impossible proof—a serial number—to claim what’s rightfully ours.

This isn’t just negligence; it’s a $30 billion heist orchestrated through silence and red tape. This story is about broken promises, frustrated heirs, and the relentless pursuit of justice. Because sometimes, the biggest heists don’t happen in the dead of night—they happen in plain sight, sanctioned by those who are supposed to protect us.

The Treasury Department’s refusal to release bondholder records has effectively shuttered any means for descendants to claim these assets, betraying the government’s historic assurances.

Heirs Search For Lost Savings Bonds

As an heir, I know firsthand the frustration of trying to piece together a family legacy that includes long-lost savings bonds.

When our loved ones passed, we painstakingly searched through drawers, rifled through old boxes, and examined every nook and cranny of their homes.

I scoured safe deposit boxes and dug through drawers, hoping to find any trace of the missing bonds I knew were part of the estate.

Each search brought a flicker of hope—perhaps this time, I would find what I was looking for.

But more often than not, I was met with disappointment and the realization that while some bonds surfaced, others were still missing.

Treasury’s catch-22

The U.S. Treasury Department’s policies added a layer of exasperation to this emotional process.

Without the serial numbers of the lost bonds, I could go no further. The Treasury knew the name of my relative and held records of these bonds, but they would not share that information with me. The injustice of this became all too clear: my diligence, my right as an heir, was met with an unyielding wall of silence.

This created a classic catch-22: the Treasury required serial numbers to locate the bonds, but without access to their records—records they openly admitted to having—there was no way for me to obtain the very information

Despite decades of assurances, Treasury officials have resisted calls to publish bondholder records or collaborate effectively with state unclaimed property programs.

Congress Stonewalled By Treasury

In a March 2024 letter to Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen of the Biden Administration, members of Congress criticized the Department for undermining efforts to reunite bondholders or their heirs with their rightful property. The letter highlighted that while Congress enacted legislation—notably Section 122 of the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022—to open these records for state access, the Treasury’s restrictive proposed rule made it practically impossible for states to use this information effectively.

The impact of this policy goes beyond bureaucracy; it affects real families seeking to recover their ancestors’ investments. The accumulation of unredeemed bonds, a staggering $30 billion, represents not only a financial misstep but a moral failing by the Treasury to uphold its commitments.

The failure to fulfill the promises made to bond purchasers during World War I and World War II resonates especially sharply when considering how vital these investments were to households of modest means.

In an era when families invested their savings to support their country and secure a financial foothold, the Treasury’s refusal to facilitate access to bondholder records is an affront to their trust and legacy.

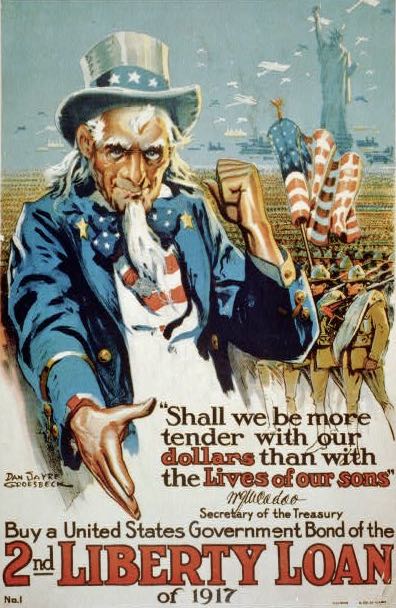

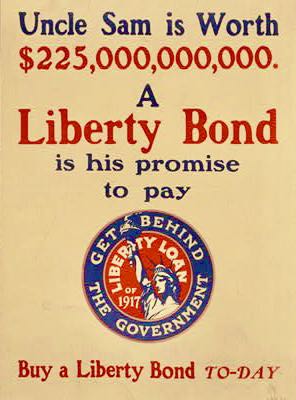

The Birth of Liberty Bonds – World War I

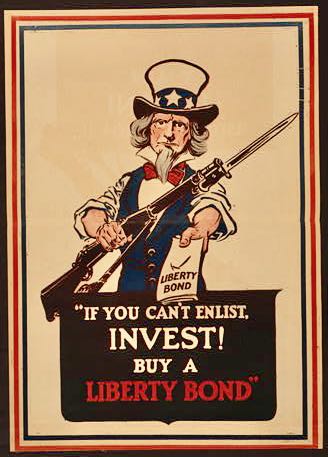

The story of how America’s war bonds transformed ordinary citizens into investors and how today’s Treasury Department has abandoned those investors’ descendants begins during World War I with the sale of Liberty Bonds.

The Liberty Bond drives of World War I persuaded tens of millions of American households to buy government bonds, which were sold in denominations as low as $50 and could be purchased in installment plans.

The scale of the expenditures resulting from the American participation in World War I was unprecedented. For each of the years 1913 through 1916, total expenditures of the federal government were less than $750 million.

By 1919, expenditures grew to $18.5 billion, a nearly twenty-five-fold increase.

Treasury Secretary William McAdoo faced a crucial decision between levying higher taxes or paying for the war with debt.

Opponents of increasing taxation to finance the war argued it would reduce support for the war by the wealthy.

In the end, taxes financed about a fourth of the cost of the war. Ordinary Americans financed the rest by buying Liberty Bonds.

The Treasury Secretary looked back to the Civil War for ideas about how to organize an effort to market war bonds on a mass scale.

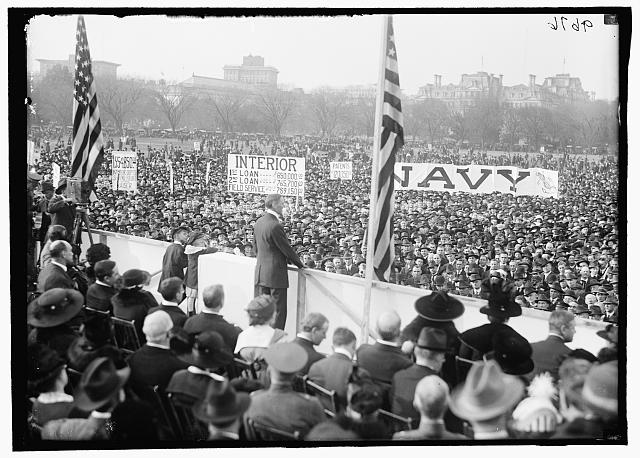

The Launch of Liberty Loan Drives

In 1917, the U.S. government launched the first of four Liberty Loan drives. A fifth and final Victory Loan drive was after the Armistice in 1919.

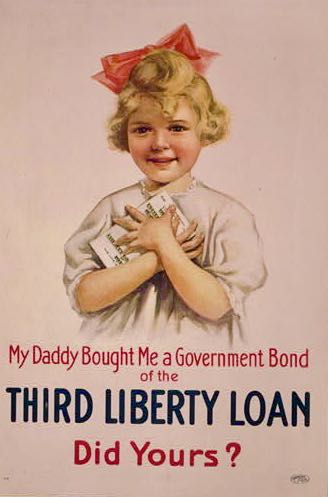

The government achieved extraordinary participation rates through a sophisticated combination of accessible pricing, community engagement, and patriotic appeals.

The marketing campaign featured dozens of posters, billboards, nationwide parades, songs, and one-step dance music titled “Don’t worry Dearie That’s a Mother’s Liberty Loan.”

Owning war bonds was seen as giving American households a financial stake in the war.

People who could not support the country by fighting could do their share in the financial trenches at home. A Poster depicting Uncle Sam holding a rifle with a bayonet stated, “If You Can’t Enlist! Buy A Liberty Bond.”

It enlisted celebrities such as soprano opera singer Geraldine Farrar in concert at the Women’s War Relief Association’s Liberty Theater in front of the New York Public Library.

Celebrities Promote Bond Sales

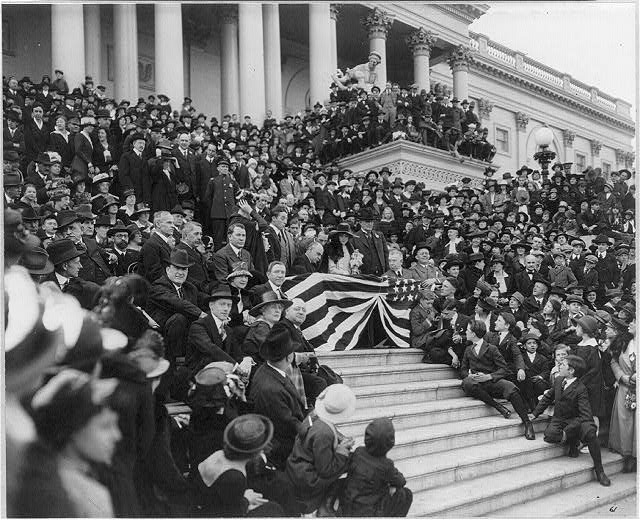

Movie stars Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford sold Liberty Bonds on the steps of the Capitol.

The Four Minute Men, a national network of volunteers authorized by President Woodrow Wilson, delivered patriotic speeches during the four minutes between reels changing in movie theaters across the country. It is simply a question now of the survival of autocracy or democracy.

Printed for the second drive, a poster shows Uncle Sam gesturing toward troops, ships, and planes around the Statue of Liberty. “Shall we be more tender with our dollars than with the Lives of our Sons?”

A poster showed a cute little girl with a big red bow in her blonde hair clutching a Liberty Loan bond, asking, “My daddy bought me a government bond of the Third Liberty Loan–Did yours?”

Former President Teddy Roosevelt Stumps For Liberty Bonds

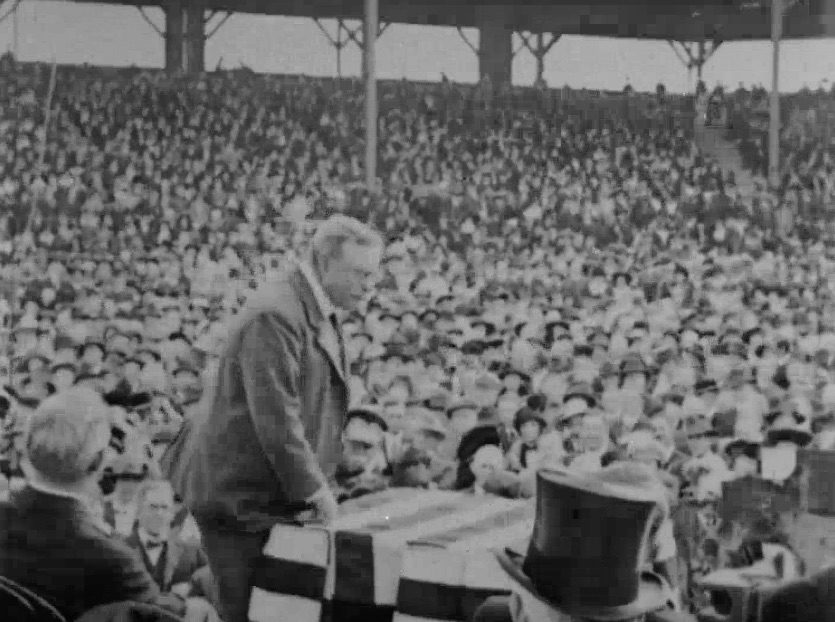

On September 28, 1918, Theodore Roosevelt spoke at the opening of the fourth Liberty Loan campaign in Oriole Baseball Park, Baltimore, Maryland.

Roosevelt wore a mourning armband for his youngest son, Quentin Roosevelt.

The youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt, he interrupted his undergraduate studies at Harvard to serve in the First World War. Less than a year after he arrived in France, his plane was shot down by enemy fire.

The twenty-year-old lieutenant, a pilot in the 95th Aero Squadron, was killed less than a year after he arrived in France.

His plane was shot down behind enemy lines by a German ace.

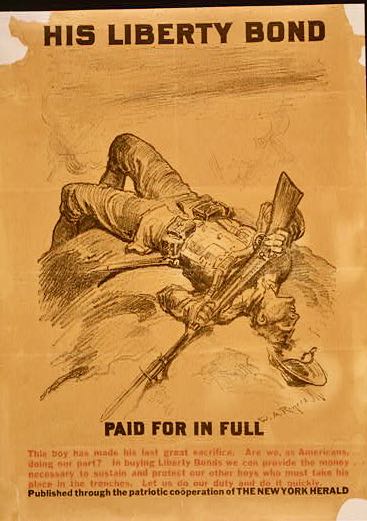

A New York Herald newspaper editorial featured a sketch of a dead U.S. soldier on the battlefield titled “His Liberty Bond, Paid For In Full. It stated, “This boy has made his last great sacrifice. Are we, as Americans doing our part? In buying Liberty Bonds we can provide the money necessary to sustain and protect our other boys who must take his place in the trenches. Let us do our duty and do it quickly.”

Marketing Strategies & Publications

The marketing was sophisticated and multi-layered. The Minneapolis Federal Reserve distributed “The Liberty Bell” newsletter, while the Chicago Fed sent “War Loan Reveille” to 3,600 local newspapers and bankers. Specific appeals were written for trade journals and fraternal publications ranging from Hoard’s Dairyman to the Wisconsin Medical Journal.

All manner of civic and economic organizations were recruited. The National Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, created in May 1917 and chaired by Secretary McAdoo’s wife Eleanor, worked through existing women’s groups and became a formidable sales force, often outraising their male counterparts.

Even America’s clergy were enlisted. On Liberty Loan Sundays, ministers took their pulpits to preach the virtues of bond buying, using model sermons distributed by Federal Reserve Speaker’s Bureaus.

The Committee on Public Information (CPI) played a crucial role, becoming what historians call “a gargantuan advertising agency the like of which the country had never known.”

Its Four Minute Men program deployed 75,000 volunteer speakers across over 5,000 communities, delivering over seven million speeches promoting bond purchases.

Purchasers would receive war bond buttons to show proof of their support.

All told, the five bond drives raised $24 billion, equivalent to more than $5 trillion today.

The bonds were deliberately structured for working-class buyers – sold in denominations as low as $50 (equivalent to about $673 today) and available through installment plans.

For example, a $50 Liberty Bond could be purchased by a payment of $4 upfront and then twenty-three weekly payments of $2. This accessibility was revolutionary – making government securities available to Americans who had never before owned financial assets.

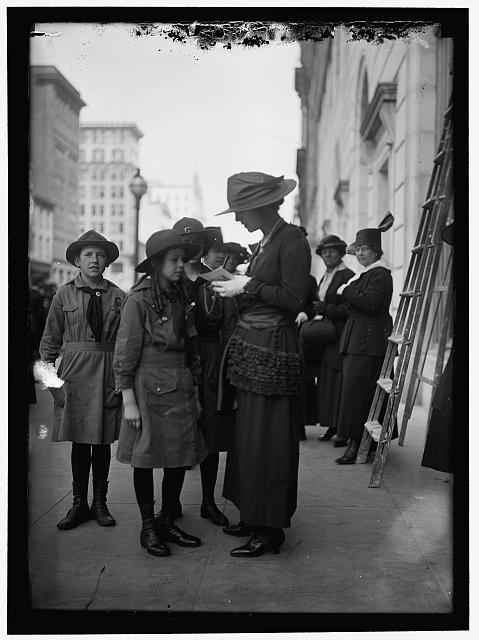

The marketing effort was equally innovative. Rather than relying on traditional financial networks, the government enlisted an army of volunteers from civic organizations. The Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, women’s clubs, religious groups, and labor unions joined the effort.

During the fourth Liberty Loan drive alone, more than two million Americans volunteered as salespeople.

Working Class Households Answer The Call

The success was remarkable. In a study titled “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War One,” economist Eric Hilt and political scientist Wendy Rahn found that about 67% of urban, working-class households purchased Liberty Bonds in 1918-1919. To put this in perspective, they note that among modern households of equivalent income today (adjusted for inflation), only 11.4% own stocks directly or indirectly through mutual funds or retirement accounts.

Posters promised to repay the debt of its citizens, stating, “Uncle Sam is worth $225 Billion–A Liberty bond is his promise to pay back a Liberty bond today.

In the decades after World War I, the federal government continued promoting bonds to ordinary households, albeit with varying levels of success. Among the most significant initiatives were the Series E bond sales during World War II.

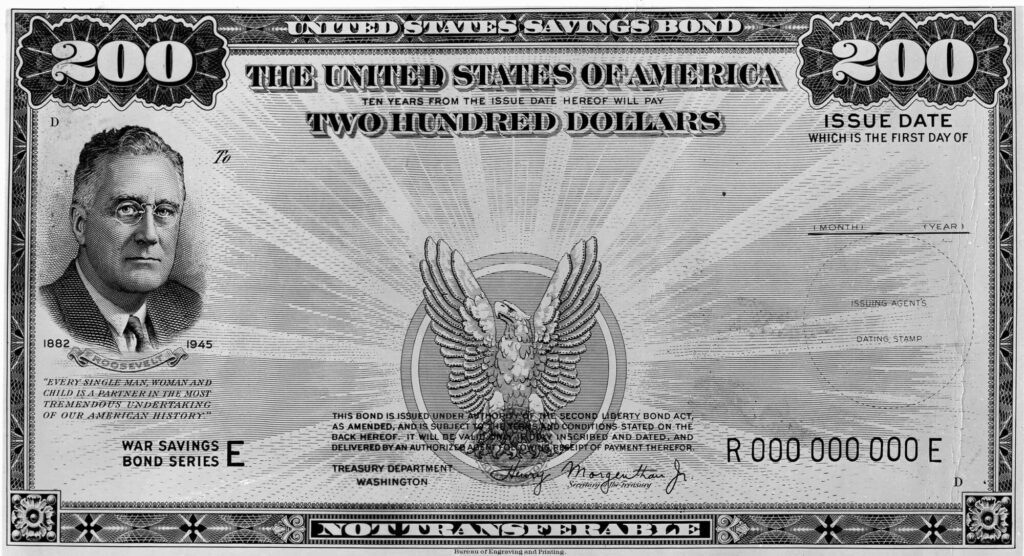

FDR’s Baby Bonds

In 1935, the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) introduced the first

“Baby bond” officially known as the Series “A” United States Savings Bond.

The government was about to undertake a number of programs to relieve the unemployment situation stemming from the Great Depression.

An appropriation bill for four billion and eight hundred million dollars was pending — a huge sum for those days.

This required deficit financing. Treasury officials wanted to avoid having the new securities held by relatively few buyers — the banks and wealthy individuals.

They believed that widespread holding of the national debt was a sound principle of government financing.

The Savings Bond was an instrument of government savings bonds, distinct from Liberty Bonds, as they were not marketable securities—they couldn’t be traded or fluctuate in value.

The Promise To Repay Bondholders

It recorded that John Doe had loaned his government a number of dollars which the Treasury promised to pay back with interest at the end of so many years.

If John Doe needed the money in the meantime, he could redeem his bond with interest.

FDR’s Savings Bond Objectives

The Savings Bond program established three objectives:

1. To instill into the minds of the American people the habit of thrift;

2. To educate the people with respect to government Securities;

3. To bind the people closer to their government, not only in financial affairs but for its total well-being — a Savings Bond was “A Share in America.”

These bonds were offered in denominations as small as $25 at a purchase price of $18.75 and included a fixed schedule of redemption values, representing the initial purchase price plus accumulated interest. Designed to finance the federal government and provide a practical savings tool for households, these bonds quickly gained popularity.

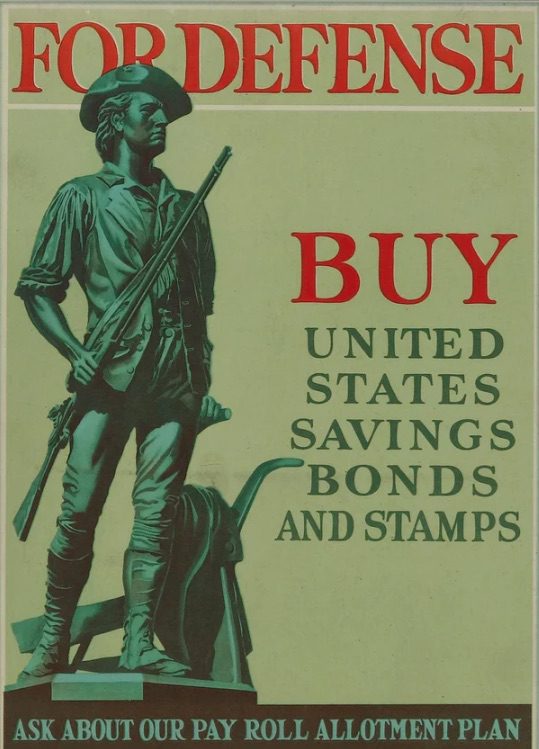

World War II Defense Bonds

As World War II began, American policymakers faced a similar range of financing options to those used by Secretary McAdoo in World War I. President Franklin D. Roosevelt favored heavy taxation and a forced savings program through payroll deductions, which could quickly raise funds and curb inflation.

However, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau believed the American public would voluntarily lend their money out of patriotism and shared sacrifice.

Morgenthau, who was instrumental in setting up the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Public Works of Art Project in the 1930s, aimed to fund much of the war through borrowing, particularly via Series E savings bonds, and renamed defense bonds to reflect their wartime purpose.

The Chicago Operation

In 1942, the Division of Savings Bonds was moved from Washington, D.C., to Chicago — a central shipping point. Many of America’s largest printing plants were located in the Midwest. The move increased efficiency and ability to handle an extremely difficult task.

To picture the magnitude of the operation by this Division during the War Bond program, by 1945, the division occupied over a million square feet of floor space in three buildings in Chicago — the Merchandise Mart, the Furniture Mart and the Nash Building.

They had the largest card file in existence, consisting of 10 million stubs of Series A-D bonds, one billion stubs of Series E bonds, three million stubs of

Series F bonds and eight million stubs of Series G bonds.

Nearly all promotional material — posters, leaflets, and booklets were received from the printing plants, packaged, and mailed from there.

In addition, all processed letters, press, and radio releases were printed and mailed. It was said that the business machine installation handled the largest volume of material anywhere. The operation required an average of 11,000 employees.

Early in the planning, it was agreed to have two methods of installment buying of Defense Bonds — payroll savings and a stamp to be sold and turned in for a bond.

The payroll savings had to have the cooperation and approval of labor and management, which was a part of organization and sales promotion.

Introduction Of The Minute Man Symbol

The stamps needed a name and symbol to aid their introduction and acceptance by the people. After rejecting numerous designs, the Defense Bond used Daniel Chester French’s famous statue of the Minute Man.

It was a familiar image used in school textbooks across the country. And it was a civilian and not a military device.

For over 30 years, it has been the symbol of the Defense, War, and Savings Bonds programs.

On April 19, 1941, the 166th anniversary of the Battle of Lexington, the first shipments of Defense Savings Stamps bearing the slogan, “America on Guard,” were shipped to post offices nationwide with the stamp albums.

The early Defense Bond Staff comprised about forty sales and promotion employees representing various talents. Some were college graduates with more than one advanced degree.

There were lawyers, doctors, engineers, writers, reformers, advertising executives, and newspaper reporters. Some were working for a dollar a year, and most were working for salaries far below what they earned or could earn in the private industry.

The organization contained experts in fundraising supported by sections for radio, motion pictures, and special events.

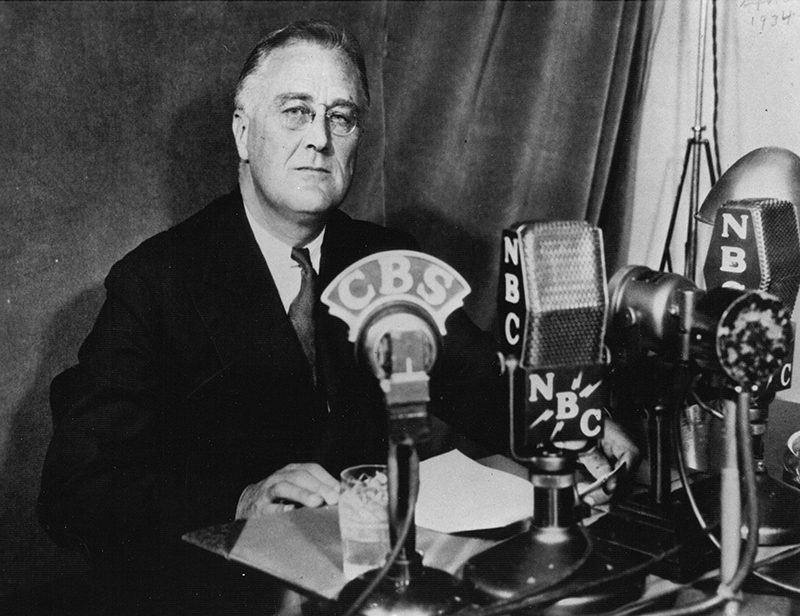

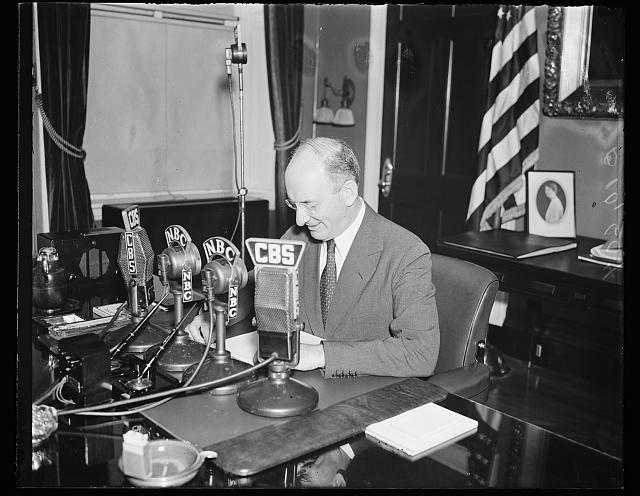

FDR Launches Defense Bond Program

On April 30, 1941, at 9:20 P.M. EST, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sat at his desk in the White House behind a battery of radio network microphones.

Newsreel cameramen adjusted their lights and lens. Radio technicians listening on their headphones tested audio levels. Secretary of Treasury Henry Morgenthau sat beside the President.

A red light blinked at 9:30 P.M. The film cameras started quietly rolling.

Secretary Morgenthau spoke: “Tomorrow morning, the government of the United States provides one answer to the question that patriotic Americans have been asking ever since the national defense program was undertaken.

‘The question has been: ‘What can I do to help?’ As the Defense Savings Bonds and Stamps go on sale tomorrow in every state and county, city and town in America, it will be possible for everyone — literally everyone — to take part in the National Defense effort.”

At the close of his statement, Secretary Morgenthau obtained the President’s order for a $500 Series E Defense Bond to be delivered the next morning when the new bonds were officially placed on sale.

The radio networks then switched to Kansas City, where Postmaster General

Frank Walker announced the Defense Savings Stamp program and added that he was reserving the first stamp for the President.

Back in Washington, the President spoke briefly but eloquently, urging patriotic citizens to form a “partnership between all of the people and their government –entered into to safeguard and perpetuate all those precious freedoms which the government guarantees by investing their savings in Defense Bonds.”

Thus began the Defense Savings Bonds program.

Record-Keeping Promises

New York Post reporter Sylvia Porter, one of the leading personal finance columnists in the nation, broke the story to her newspaper’s readers.

Tomorrow, in 16,000 post offices and thousands of banks and other special agencies, defense securities costing from 10 cents to $10,000 will go on sale.

This starts 1941’s defense loan campaign. Before it is completed — a year or many years from now — billions of dollars will have been borrowed by the Treasury from the little people of America. Tens of millions will own government bonds for the first time, will have savings plans based on their purchases of securities, will have a direct financial interest in their Treasury.

No matter what your income or your financial state, there are defense bonds suitable for your purchase. Everybody is covered in the three types of bonds being offered by Secretary Morgenthau — from the schoolboy who can afford a 10 cent weekly contribution to the wealthy individual who can pick up $50,000 of the bonds in one operation.

For nearly a decade after the debut of one of America’s most influential financial columns, the identity of its author remained a mystery.

Known only as “S.F. Porter,” the writer captivated readers with insightful financial advice in the New York Post, becoming one of the most trusted voices in personal finance journalism during the early 1930s.

It wasn’t until 1942 that the truth emerged: the widely assumed “wise old man” behind the column was, in fact, Sylvia Porter, a trailblazing woman who had quietly redefined financial journalism and earned a devoted following.

An Advertising Blitz

Like savings bonds, the Series E bonds were promoted through large-scale and highly aggressive bond drives. Morgenthau recruited Peter Odegard, a political scientist from Amherst College, to design the Treasury’s bond-selling strategy.

A Bonds at War film showed tanks, artillery, and other war equipment in action as its narrator explained how many bonds were needed to pay for each.

One scene shows paratroopers jumping out of a transport plane, filling the sky with silk canopies of parachutes. The narrator says, “Each one of those men is supported by three fifty-dollar war bonds. That’s what a parachute costs.”

The plan borrowed heavily from the Liberty Loan campaigns of World War I. Bond sales were concentrated into short, intensive drives, with commercial banks acting as issuing agents, often encouraged by the American Bankers Association. Publishers donated advertising space, and volunteers from civic, religious, and business organizations joined the effort.

Department stores were even used as promotional venues. In one example, a Younkers store in Des Moines, Iowa, dramatically lowered a coffin labeled “Adolf Hitler” from the ceiling every time a bond was sold. A sign urging “Help Us Bury Hitler” stood next to a devil with a pitchfork emerging from the ground to take a jab at Hitler’s lowering coffin.

The Treasury also created a robust propaganda apparatus, including the Division of Press, Radio, and Advertising and a Women’s Section led by Harriet Elliott, dean of women at the University of North Carolina.

Morgenthau’s wife volunteered with the Women’s Section to channel her energy as their son served in the armed forces. Throughout the war, approximately five to six million volunteers canvassed their communities, personally urging neighbors to “buy our boys back.” Research by social psychologists in the Division of Program Surveys within the Department of Agriculture revealed that this personal outreach was particularly effective.

In 1941, leading celebrities in the entertainment field rallied for the Bond program. After the United States entered the war, the entertainment world went all out for bond promotion. Through the motion picture industry, the program secured top stars, featured players, and starlets at bond rallies.

Carol Lombard Pays With Her Life Selling Defense Bonds

Carol Lombard, one of the leading ladies of Hollywood, was in great demand for war bond rallies.

The beautiful starlet volunteered to attend a War Bond Rally in Indianapolis, Indiana, her home state, on January 15, 1942.

Twenty thousand people turned out to see the starlet. Lombard raised more than two million dollars in defense bonds in that single evening.

She, her mother, and the press agent for her husband Clark Gable had been scheduled to return to Los Angeles by train, but Lombard was eager to reach home more quickly and wanted to travel by air.

The trio boarded a TWA flight with 22 passengers. After stopping in Las Vegas to refuel, the airliner crashed into a mountain at night, killing the 33-year-old actress and everyone else, including 15 army soldiers.

Safety beacons normally used to direct night flights had been turned off to prevent Japanese bombers from flying into American airspace from the Pacific Ocean.

President Roosevelt issued a message stating, “She gave unselfishly of her time and talent to serve her government in peace and war… She loved her country.”

The text of Lombard’s last plea for the public to purchase defense bonds was placed in the Congressional Record.

Treasury Secretary Morgenthau Promises Access To Defense Bonds

A few days later, Treasure Secretary Morgenthau assured United Automobile Workers they would always be able to access their investment in Defense Bonds. In his speech on January 25, 1942, Morgenthau said quote, I am often asked three questions about Defense Bonds which must, I am sure, be in your minds. The first is, Can I get my money out if I need it? The answer is yes–any time after sixty days from the date you bought your bond. The second is, What happens if I lose my bond? The answer is that we at the Treasury have a record of every bond and its owner; we can supply you with another if you identify yourself, and we will be glad to keep your bond for you at the Treasury if you wish us to keep it in the safe for you. The third question is, Will I lose money on these bonds the way so many people lost on the Liberty Bonds? The answer Is that you can’t lose. These Bonds, unlike the old Liberty Bonds, are registered in your name. You cannot trade them on the market or offer them in payment of debt. You will always get back from the government your one hundred cents on every dollar, and the longer you hold time, the more they will grow in value. End quote.

The Defense Bond program focused on the great mass of people–the small investor. It promoted payroll savings with the slogan, “Let’s Make Every Pay Day Bond Day.”

Sylvia Porter revealed to her readers plans for a house-to-house canvass by volunteer workers. “The volunteers who will be going around from house to house will try to teach the millions who today are spending to the limit of their earnings, the evils of their actions. They’ll attempt to sell bonds on the spot’”

The volunteers carried pledge cards to be signed to purchase Defense Bonds or Stamps every payday.

The Defense Bond Program blitzed the American public with its promotional campaigns in newspapers and magazines and on radio, stage, and screen. Bugs Bunny cartoons promoted war bonds. Walt Disney permitted 22 characters, including Donald Duck, Bambi, and the Seven Dwarfs, to be used on bonds purchased for babies and small children.

The Spiralling Cost of World War II

By the start of 1943, the cost of the war had risen to more than 200 million dollars a day.

Treasury Secretary Morgenthau, in an address to the American Bankers Association, urged, “Our job is to get every dollar beyond what is actually needed for living expenses — to get the people to understand why real sacrifice — giving up luxuries and unnecessary spending — is expected of them. The most satisfactory and efficient way

to get this money is through increased savings on the Pay-Roll Savings Plan.”

Morgenthau noted that Sylvia Porter, the financial writer, in her column in the

New York Post assisted us in this project by printing a series of “Questions – Answers” on War Bonds.

Popular Financial Columnist Reinforces Promises Of Access

On February 19, 1943, Porter wrote her sixth series as follows:

“With close to 50,000,000 of us owning war bonds and the total increasing every day, it’s probably to be taken for granted that many of us are being careless and are misplacing or losing our certificates — and judging by the War Bond questions received by the Post this week, that assumption is entirely justified.

Oddly enough, three readers wrote in simultaneously, posing different problems arising out of loss of War Bonds. And each one wants to know how he or she can go about tracing ownership, proving loss, and replacing the security.”

“M. G. of Brooklyn, however, ‘thinks’ she has lost one of three bonds she and her husband bought in 1942. Her impression is that they purchased three bonds but she can only find two. And she asks, how can I go about finding out how many bonds are registered in our names?”

Porter reinforced Morgenthau’s promises, assuring her readers that, “Luckily, when we buy War Bonds, the Government registers them in our names and keeps the lists up-to-date at all times at the Treasury Department in Washington. So the problem of loss is easily solved.”

Porter suggested to the reader, identified by her initials M.G. that “The best step, therefore, is to go direct to the Federal Reserve Bank and submit proof of identity, address, et cetera. The Reserve Bank will check on the bonds registered under M.G.’s name and let her know what securities have been issued to her. If she does own three and can prove loss of one, a duplicate of the bond she cannot find at home will be issued by the Treasury.”

Cost Of War In The Pacific

After the defeat of Germany, the war bond drive stressed the cost of the mounting war in the Pacific against Japan, stating the U.S. needed more of everything: More B-29 Superfortresses that cost $600,000 each. More P-47 Thunderbolts that cost $50,000 each. More M-4 tanks with bulldozer blades that cost $67,417 each. More amphibious tanks — more aircraft carriers — more supply ships — more gasoline and oil than it took for the invasion of Europe.

The American people answered the call.

World War II’s eight loan drives raised more than $146 billion from individuals.

Modern Crisis Of Confidence Begins

After the war, the Series E Defense Bond became a peacetime security in which American families continued to invest, either at their workplaces through payroll deduction or over the counter.

In 2003, the U.S. Treasury eliminated its marketing efforts for savings bonds and, in 2011, eliminated paper bonds, which reduced the appeal of savings bonds as gifts.

Worse yet, bondholders could not just waltz into their local bank to cash in savings bonds. They are no longer as good as cash even though the fine print on the back of savings bonds usually reads. “Payable by any financial institution.”

Bureaucratic Road Blocks To Redeeming Savings Bonds

Today, some banks flat refuse to redeem savings bonds. Some customers have undergone a months-long odyssey to help elder family members cash their savings bonds.

In 2023, the daughter of a mother in hospice care discovered $300,000 in savings bonds stuffed inside a Tupperware container.

It took five months for the funds to arrive from the Treasury.

U.S. Treasury Reneges On Decades Of Promises

The Treasury Department has abandoned the grassroots principles of patriotism by breaking the wartime promises of its Secretaries.

Remember the assurance Henry Morgenthau gave to autoworkers during a World War II bond drive? What happens if I lose my bond? The answer is that we at the Treasury have a record of every bond and its owner; we can supply you with another if you identify yourself,

More than 87 million bonds remain unclaimed – their records sealed from public view.

Congress attempted to address this through the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022, directing Treasury to share bond records with state unclaimed property offices. These offices maintain searchable databases that have proven highly effective at reuniting people with lost assets.

However, the Treasury’s response has been to propose rules that would prevent states from publicizing enough information for heirs to identify unclaimed bonds.

This stance directly contradicts the historical promise of transparent record-keeping that made the bond programs successful in the first place.

In a March 18, 2024, letter to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, members of Congress complained that the department was not following the letter and spirit of the law to assist states in returning the assets to bondholders or their heirs.

Negative Impact On Minority Communities

The letter noted that, Further resolving the backlog of unclaimed property is a matter of righting past wrongs and equal treatment under the law. Due to state-enforced racial segregation and subsequent exclusion from traditional banking systems in the early-to-mid 20th Century, African American families and other minority groups invested in savings bonds at higher rates. Given this fact and that most of these matured bonds at Treasury are from the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, it would follow that African Americans and other minority groups represent a high percentage of unclaimed bondholders.

As the Treasury continues to resist transparency, those billions in unclaimed bonds stand as silent testimony to promises made – and broken – to generations of patriotic Americans who answered their country’s call in its hour of need.

The success of the original bond programs was built on trust in government record-keeping and accessibility. Treasury broke a promise that had been paid for in blood during the war years.

Take Action: Demand Accountability for $30 Billion in Unclaimed Bonds

The U.S. Treasury is holding over $30 billion in unredeemed savings bonds, denying rightful heirs the ability to claim their family’s legacy. This is your chance to make a difference.

Contact the chairs of the tax-writing committees in Congress and urge them to hold the Treasury accountable.

Ask them to demand transparency, enforce existing laws, and ensure the release of bondholder records so families can reclaim what is rightfully theirs.

Make Your Voice Heard! Write, Call, or Email

Mike Crapo (R-ID)

Chair – Senate Finance Committee

239 Dirksen Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. 20510

202-224-6142

https://www.crapo.senate.gov/contact/email-me

Jason Smith (R-Mo.)

Chair – House Ways and Means Committee

1011 Longworth House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

Phone: 202-225-4404

https://jasonsmith.house.gov/contact

Help end this bureaucratic theft and ensure justice for millions of American families.

Until Congress and the President act, millions of American families will continue to be denied their rightful inheritance while the Treasury Department maintains its grip on records that were never meant to be secret.

It’s a situation that would have been unthinkable to the generations who purchased these bonds, secure in the government’s promise that their investment would always be traceable and redeemable – a promise that, decades later, remains unfulfilled.

CLICK TO LISTEN TO THE PODCAST EPISODE

FOLLOW the True Crime Reporter® Podcast

SIGN UP FOR my True Crime Newsletter

THANK YOU FOR THE FIVE-STAR REVIEWS ON APPLE Please leave one – it really helps.

TELL ME about a STORY OR SUBJECT that you want to hear more about

Step into the storied halls of the Texas Prison Museum and uncover the gripping tales of infamous inmates, daring escapes, and the history of justice in the Lone Star State.