The Start of a Gruesome Career

Mike Cox’s reporting on the gritty world of the police beat became a lifelong career steeped in blood, ink, and the relentless pursuit of the truth. Today, Cox is one of Texas’ most respected chroniclers of both real and historic crime.

“I’ve never really counted how many murders I’ve been involved in,” Cox said, quickly clarifying, “not as a perpetrator, of course, but as the person either writing about the murders or informing the media.”

From covering hundreds of murders to serving as the chief of media relations for the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS), Cox has straddled the line between horror and history for decades.

Mike was the DPS spokesman at many of the crime scenes that I covered as a reporter, including the Luby’s Cafeteria Massacre, the Branch Davidian Siege, and the standoff between the Texas Rangers and the Republic of Texas separatists in Fort Davis.

He is a seasoned author with multiple books detailing the history of the legendary Texas Rangers. But despite his vast historical knowledge, Cox’s life remains deeply intertwined with modern-day crime, particularly one of the most notorious serial killers in U.S. history: Henry Lee Lucas.

A Confession that Stunned the Nation

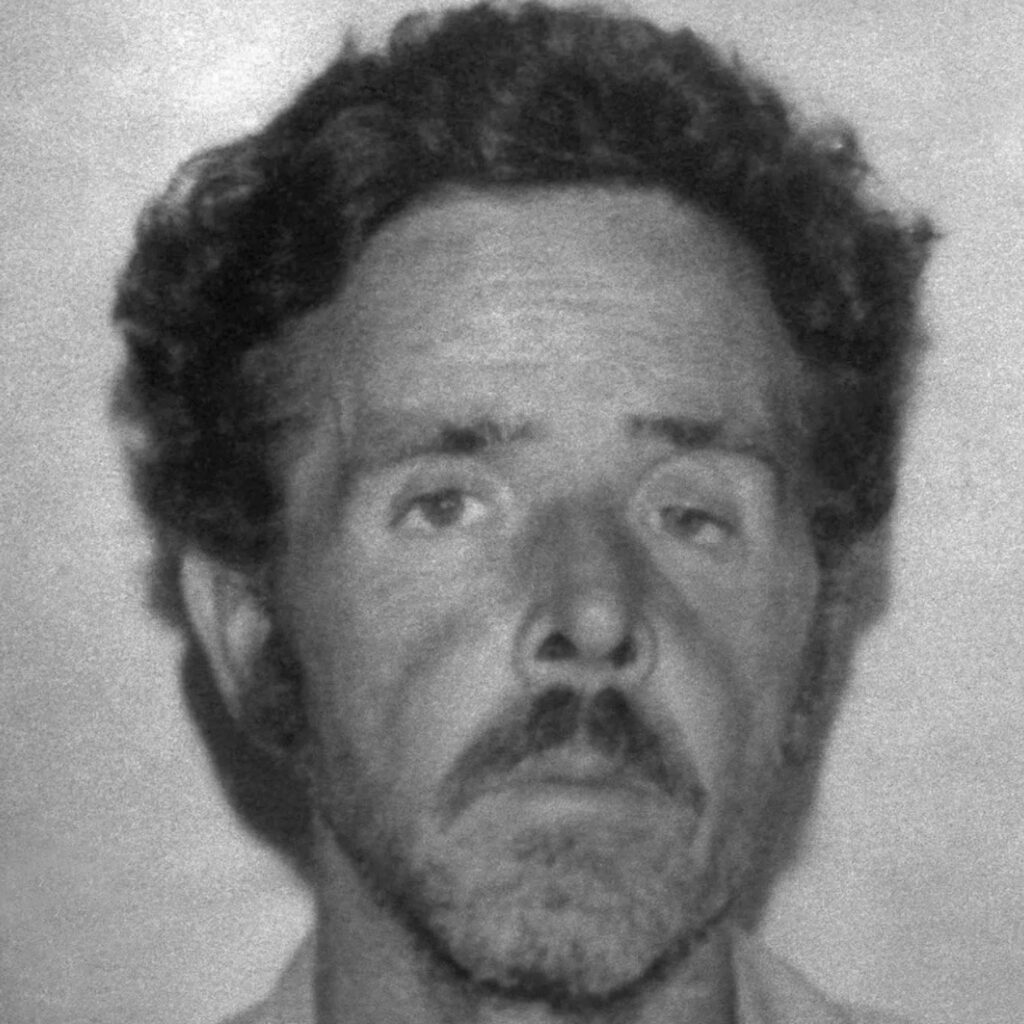

In June 1983, Cox was working as a police beat reporter for the Austin American-Statesman when he heard a tip about a suspect claiming to have killed multiple women. The suspect, Henry Lee Lucas, had been arrested in North Texas and was being investigated for a potential string of murders.

Cox wasted no time. He received permission to fly to Dallas, rent a car, and drive to Montague County, a rural area located near the Texas-Oklahoma border. He had no idea that what he would uncover there would shake the country.

“Lucas was this snaggle-toothed drifter with a glass eye, and when I saw him in court, he blurted out something that made everyone’s head spin,” Cox said. “He was being arraigned for the murder of an elderly woman in Montague County when he said, ‘What about the other 100 women I’ve killed?’”

That stunning confession landed Cox’s story on the front page of the Austin American-Statesman. His photographer captured the now-iconic image of Lucas being escorted back to jail, part of what journalists call the “perp walk.” Cox was the only reporter from a major city daily at the courthouse that day, giving him a national scoop.

The media quickly descended on Montague County. The sleepy courthouse became the center of a surreal media spectacle, with news helicopters swirling overhead. Lucas’s confession exploded into a nationwide story as the public tried to wrap its head around the idea of a man who claimed responsibility for over 100 murders.

The Numbers Begin to Climb

Lucas’s initial confession was shocking enough, but what followed was even more bewildering. As law enforcement from around the country began questioning him, Lucas cheerfully confessed to murder after murder. Eventually, he claimed to have killed more than 600 people.

“He was absolutely going nuts,” Cox said. “At one point, Lucas even claimed to have killed people in Japan. It became ludicrous, and yet law enforcement was swallowing it—except for the more obviously ridiculous claims.”

Lucas’s claims drew national attention, in part because of how easily police seemed to accept his confessions. Some saw it as an opportunity to close unsolved cases, no matter how flimsy the evidence linking Lucas to the crime.

One of the most notable cases Lucas confessed to was the murder of a woman known only as “Orange Socks.” Her body had been discovered in a culvert along Interstate 35 near Austin in 1979, wearing nothing but a pair of orange socks. She had been sexually assaulted, strangled, and thrown from an overpass.

Cox would go on to conduct a series of exclusive interviews with Lucas while the killer was incarcerated in the Williamson County jail. The access granted to Cox was extraordinary—he would meet with Lucas weekly, recording hours of interviews.

“Sheriff Jim Boutwell let me have a standing Tuesday night date with Lucas,” Cox recalled. “I’d sit right there outside his cell, sticking my tape recorder through the bars.”

What Lucas told him was both horrifying and, in many cases, implausible. Lucas bragged about killing his victims in unimaginable ways—crucifying them, running them over with cars, even filleting them like fish. He claimed to have provided the cyanide that led to the deaths of more than 900 people in the infamous Jonestown mass suicide. The stories seemed too far-fetched to believe, but they were still captivating to law enforcement and the public alike.

Reality Catches Up

While Lucas’s confessions grabbed headlines, some investigative journalists began to cast doubt on his stories. Hugh Aynesworth, a veteran reporter from Dallas, was one of the first to debunk Lucas’s claims, proving that he couldn’t have been at every murder scene he confessed to.

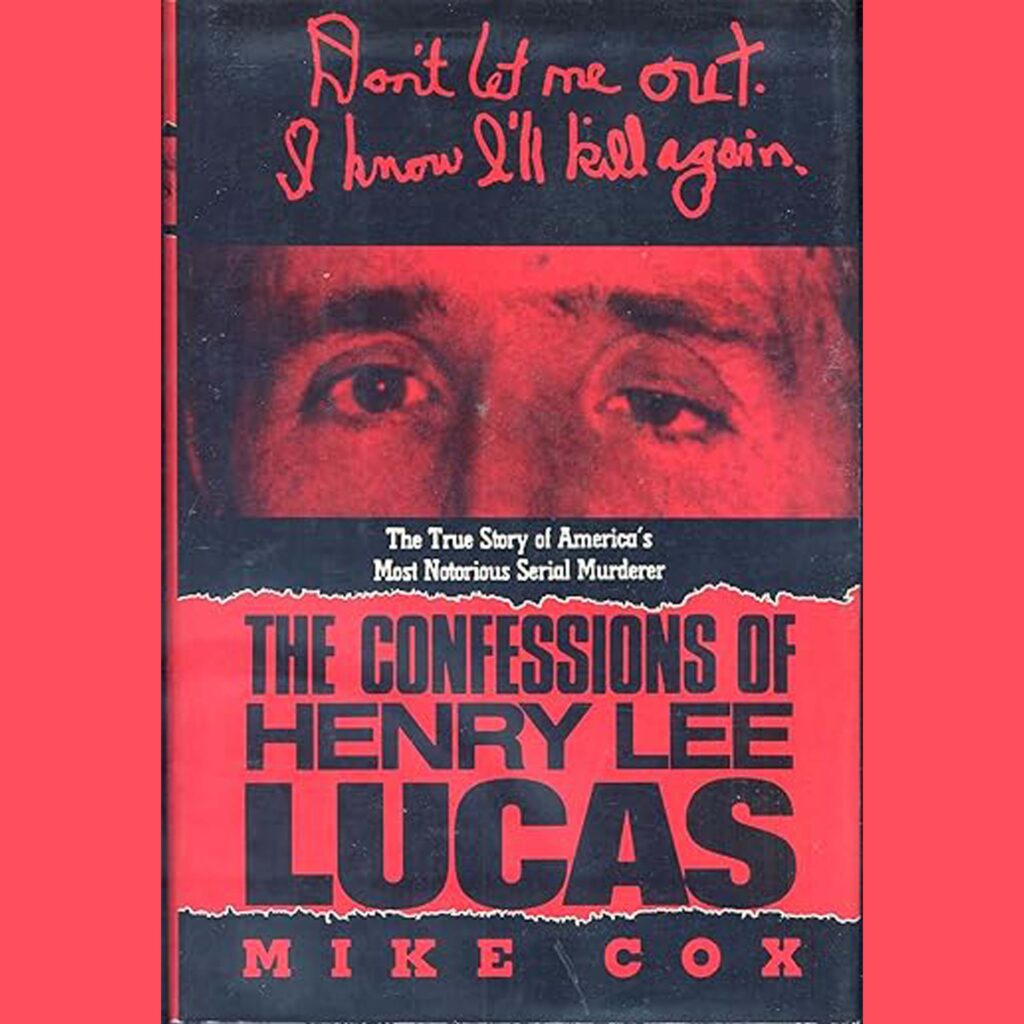

Cox, too, began to realize that much of Lucas’s story was, as he put it, “spun out of whole cloth.” In 1991, Cox published The Confessions of Henry Lee Lucas does not doubt that Lucas was a killer—there was substantial evidence tying him to several murders, including that of his mother and his girlfriend, 15-year-old Becky Powell.

“He definitely killed his mother,” Cox said. “I went to Ohio and held the knife he used to stab her. Lucas’s girlfriend, 15-year-old Becky Powell, lived with him while he worked as a handyman for 82-year-old Kate Rich in Montague County. After an argument with Powell, Lucas brutally stabbed her to death, dismembered her body, and scattered the remains across a field.

Just three weeks later, back in Montague County, Lucas offered 82-year-old Rich a ride to church. Instead, he stabbed the elderly woman and stuffed her body into a drain pipe

Still, the scale of Lucas’s confessions was vastly exaggerated. In many cases, Lucas had been nowhere near the crime scenes. But that didn’t stop law enforcement from using his confessions to clear hundreds of cold cases.

“I’ve talked to Texas Rangers who were there when Lucas led them to bodies,” Cox said. “He’d say, ‘Turn left here, turn right here,’ and it was uncanny how accurate he was. But at the same time, he was making up a lot of it.”

The “Orange Socks” Case and Lucas’s Final Days

In 1984, a Texas jury convicted Henry Lee Lucas of capital murder in the case of the woman known as “Orange Socks.” Despite a lack of physical evidence connecting Lucas to the crime, his confession was enough to secure the conviction. It was the only one of Lucas’s 11 murder convictions that resulted in a death sentence.

However, Lucas later recanted this confession, along with hundreds of others. As his fabrications unraveled, they exposed a disturbing reality—many law enforcement agencies were more interested in closing cases than in verifying the truth behind Lucas’s claims.

Lucas himself admitted that he had intentionally misled investigators, stating, “I wanted to make a mockery of law enforcement and did everything I could to discredit the badge.”

In 1998, after Lucas had spent 13 years on death row, Governor George W. Bush commuted his sentence to life in prison. The decision came after evidence suggested that Lucas may have been in Florida at the time of the “Orange Socks” murder.

Decades later, in a breakthrough, the “Orange Socks” victim was identified through her sister’s DNA as 23-year-old Debra Jackson, who had last worked at an assisted living facility northwest of Fort Worth.

Although Lucas’s death sentence was commuted, there was no possibility of his release. In addition to the life term for the “Orange Socks” murder, he was serving six other life sentences and 210 additional years for three other killings. He had been convicted of nine murders in Texas and one in West Virginia.

Lucas would spend the rest of his life in prison, where he took up painting and sold still lifes to collectors interested in art produced by a convicted serial killer. He died quietly in his sleep in 2001, suffering from heart problems.

“Unlike some of his victims, he had a peaceful passing,” remarked a Texas prison spokesman after his death.

A Legacy of Uncertainty

Despite his death, Henry Lee Lucas’s confessions continue to be a subject of fascination and controversy. While Cox is convinced that Lucas killed several people, he remains skeptical of the staggering numbers Lucas claimed.

“He fell way short of being the world’s worst mass murderer,” Cox said. “That was absolutely not true.”

Cox’s work, from his reporting on the Lucas case to his later books about the Texas Rangers, has cemented his reputation as one of the foremost authorities on crime in Texas. However, for Cox, the legacy of Henry Lee Lucas will always be one of the unanswered questions.

“It’s one of the great mysteries of 20th-century crime,” Cox said. “We’ll never know the full truth.”

FOLLOW the True Crime Reporter® Podcast

SIGN UP FOR my True Crime Newsletter

THANK YOU FOR THE FIVE-STAR REVIEWS ON APPLE Please leave one – it really helps.

TELL ME about a STORY OR SUBJECT that you want to hear more about