How Forensic Genetic Genealogy Found Distant Relative Of Killer

14-year Stephanie Anne Isaacson left her father’s apartment in North Las Vegas early on the morning of June 1, 1989.

She walked through an empty sandlot, her usual shortcut, to the Eldorado High School.

The ninth grader never made it to her 7:30 AM class. Her choir teacher noticed Stephanie missing during lunch period, but her absence was not reported.

When she didn’t return home by 4:30 that afternoon, her father, a Staff Sergeant at nearby Ellis Air Force Base, called the police.

He and his friends saddled up horses at the base’s stable and started to search the small desert area that Stephanie regularly cut through to school.

Four hours later, they found his daughter’s textbooks and keys strewn along a trail.

Investigators launched a helicopter and a ground search.

Later that evening, officers found a zigzag path where she had been dragged to foliage.

A police dog picked up the scent of her body under an orange piece of discarded carpet.

Stephanie was the victim of a blitz attack. Her black shirt was pulled up, and her jeans pulled down. Her shoes and other belongings were missing.

The freshman with shoulder-length brown hair who had last been pictured with a wide grin in her prom picture had been sexually assaulted, bludgeoned, and strangled to death.

Investigators had little to go on besides a tiny drop of semen found on the dead girl’s shirt.

They made numerous attempts to test the evidence and, in 2007, obtained the

DNA profile of the likely killer.

Police uploaded it into the FBI database called CODIS, the Combined DNA Index System.

CODIS, which became operational in 1999, contains the profiles of individuals convicted of certain crimes.

However, if an offender has not been convicted in recent years, it’s unlikely that their DNA is cataloged in the system.

Isaacson’s killer had never been convicted, and her murder remained a cold case for 32 years.

Las Vegas Metropolitan Police investigators never gave up.

In late 2021, they submitted DNA evidence, equivalent to a mere 15 human cells, to Othram, a cutting-edge forensic genomics lab located in the Woodlands, a suburb of Houston.

In contrast, a full DNA profile for CODIS contains 20 core markers–or points on the human genome required for an exact match.

Othram’s DNA technology measures information for hundreds of thousands of markers and can be used to identify distant genetic familial relationships.

In the case of Stephanie Isaacson, Othram’s genetic genealogist found a distant relative of the alleged killer in a genealogy database that law enforcement has the consent to search.

Forensic genetic genealogy led Las Vegas detectives to Darren Marchand, who had never been listed among suspects.

But Marchand had committed suicide at the age of 29, six years after the murder.

Kristen Mittelman of Othram says the Isaacson case is the tip of the iceberg of a silent mass disaster. Little attention or money is being focused on solving an estimated quarter of a million cold cases in the United States. “You know, it has really struck me after all these years that a lot of people have gotten away with murder and multiple murders. When you look at how you unravel and find out their other victims. It really is a scandal. It’s shameful when you look at it.”

Othram’s lab is nestled in a gleaming 25,000-foot office building on a serene campus. DNA analysts work inside glass-walled sterile environments. It’s not unusual to see human skulls and bones resting on lab tables. Outside the labs, some of the company’s 50 employees peer into computer screens studying DNA information. A classroom is often filled with Texas Rangers and detectives from across the country who receive training in forensic genetic genealogy.

David Mittelman, Othram’s founder, built the facility from the ground up to specialize in solving cold cases. The lab utilizes the world’s most powerful DNA sequencing technology. David and Kristen met at the Baylor College of Medicine, where they studied gene therapy and DNA repair. David earned a Ph.D. in molecular biophysics, and Kristen a Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology.

The privately held company has received $18 million in funding from the Gigafund, a venture fund known for its large investments in companies like SpaceX.

Announcements that Othram helped crack another cold case have become weekly events.

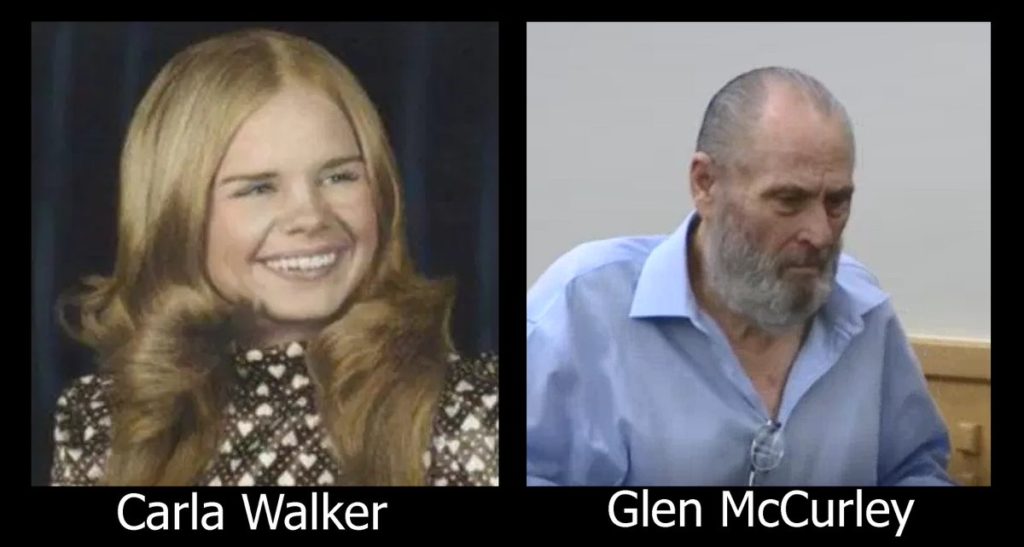

Fort Worth Cold Case detectives solved the abduction, rape, and murder of 17-year-old Carla Walker after it had gone cold for nearly five decades.

Othram matched DNA from Walker’s clothing to a distant relative of the killer profiled on a genealogy database.

Cold case investigators Jeff Bennett and Leah Wagner identified 78-year-old Glen McCurley, who was listed among the original suspects.

McCurley pleaded guilty after two days of testimony in his capital murder trial in August 2021.

Kristen Mittelman says it was one of the first time genetic genealogy evidence had been presented to a jury. “You see that people are getting away with murder. It’s more than that. I see that often people commit these horrible crimes and then live a very normal life in the middle of our society. Carla Walker’s murderer lived a mile away from the crime scene and had a wife and children. I’ve noticed this in these cases.”

Othram has received federal funding to help clear a backlog of cold cases. A test to identify a perpetrator can cost upwards of seven thousand dollars and five thousand to identify the remains of a body.

Las Vegas philanthropist Justin Woo donated money for the testing in the Stephanie Isaacson case.

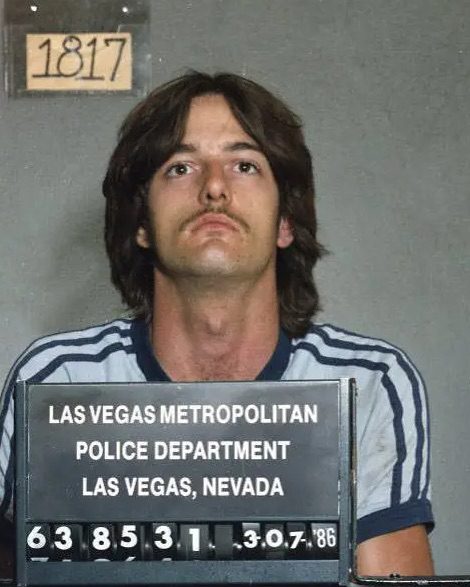

It helped police connect the DNA of Darren Marchand to her murder. At the time, he was the married father of a two-year-old daughter with a son on the way. Three years earlier, the then 20-year-old Las Vegas man had been arrested for the strangulation murder of a 24-year-old woman.

But the case was dismissed because of a lack of evidence. He died by suicide in 1995.

At the time of Isaacson’s murder, Marchand was awaiting sentencing for open and gross lewdness for exposing himself to five women. Two months after the murder, he was discharged from probation.

In the wake of the Carla Walker case, the Stephanie Isaacson case, and countless others, solved in part using Othram’s technology, Othram has leveraged crowdfunding and philanthropy to raise money and awareness for unsolved cases all over the United States. The initiative, DNASolves, aims to fund cases without traditional sources of support until one day all cases can be funded by federal and state budgets

Detective Jeff Bennett created the FWPD Cold Case Support Group, a nonprofit foundation to accept tax-deductible donations to help solve Fort Worth’s backlog of 1,000 cold cases.

Mittelman stresses that Othram’s forensic genetic genealogy findings only provide an investigative lead in cold cases. She praises investigators she has worked with for their dogged persistence. “These cases do not play out like a television police drama. The detectives have thought about this case every single day. It’s become part of who they are, part of their families, part of their lives, part of their dialect. The families of these victims have become part of their life.”

Robert Riggs is a Peabody Award-winning investigative reporter and creator of the True Crime Reporter® Podcast. He is the Executive Producer of Freed To Kill, the chilling documentary about serial killer Kenneth McDuff featured on Fox Nation. You can contact Robert by email Fan@TrueCrimeReporter.com.